Those About to Die recently joined the esteemed pantheon of Ancient Rome based drama, joining the likes of I, Claudius and HBO’s Rome but, refreshingly, telling the story of a less celebrated (and raked over) dynasty than the Julio-Claudians: that of the Flavians. And it tells their story through the lens of Rome’s public games: chariot racing, gladiators, and the various syndicates and stakeholders for whom they are the engines of wealth. It’s a good choice, particularly in the case of the Flavians, whose deathly dance with public opinion coloured their entire tenure. And it provides a baked-in excuse to widdle money all over the screen in the form of a fully populated Circus Maximus and the heart-pumping, limb-severing action that occurs within.

Roland Emmerich, the German director most associated with an alien themed mid-90s Will Smith vehicle (well, the other one), has had a mixed bag of a career. By which I mean he has produced and directed such a steady stream of hot dogshit throughout his 40-odd year career that it’s easy to forget he honestly does have his moments. I’ll always go to bat for Independence Day, which I regard as a much more cogent attempt at modernising (Americanising) The War of the Worlds than the Spielberg or George Pal efforts, with its much maligned conclusion echoing that of the original work with a knowing Y2K-era smirk. They all spectacularly missed the point, but at least ID4 had a cool skull gif and the one time only double act of Smith and Goldblum.

ID4 is a misunderstood masterpiece of a disaster movie, yes it is, shut up, which came hot on the heels of Stargate, a movie which took the core concept of Chariots of the Gods? – a wretched ahistorical treatise for racists and silly buggers – and turned it into the foundation of one of the most beloved and enduring science fiction franchises in the popular canon. What I’m saying is that prolific filmmaker Roland Emmerich has made two good films in forty years, which proves that he’s capable of good things but also that he’s unlikely to demonstrate such. So imagine my relief when he got his hands on my beloved Ancient Rome and made something… exquisite. Spectacular. Well researched. And dare I say it: nuanced.

Those About to Die is well worth the ten-hour binge. If you can hold your nose through some guffy exposition during the series opener (which thankfully calms down once the writers are confident that you can remember everyone’s names), what you get is a compelling tangle of narratives that follow some key individuals of vastly different social status as they chase their aims through the winding streets of a dangerous and dirty metropolis. From Domitian, the overlooked prince who would be Emperor, to Cala, a resourceful Numidian trader who ends up in the capital of the world desperately trying to save all of her children from punitive slavery. There are lowly gamblers with insurmountable debts to repay, street thugs who take anyone’s coin to do anyone’s dirty work, and manoeuvring strikingly close to their orbit: senators with ambitions toward the purple, the imperial throne now seen as a legitimate career goal in the wake of the year of Four Emperors.

This is a Rome of all stripes and colours, not least the four “factions” of chariot racing teams: Red, White, Green, and Blue. Their colours denote their affiliation with various deities: Mars, god of war. Zephyrus, god of wind etc. It’s telling that the real life Domitian would establish two more chariot teams: purple and gold, affiliated more or less with the twin gods of power and money. Those About to Die takes this nugget of historia – Domitian’s love of the games, and his business interests thereof — and uses it as the basis for much of the series’ overarching narrative. For Domitian, the games are a way of increasing personal wealth and establishing a loyal power base within the city. For Tenax, his lowborn collaborator who runs the stables and betting operation at the Circus Maximus, they are a rope ladder out of the gutter and a chance to extend his influence into the world of the ruling classes. His own little Empire, sprawled out in the city’s underworld.

If you listen to Mary Beard’s excellent podcast Being Roman, you’ll have heard author Robert Harris on the latest episode opining that writing historical drama is a balancing act: if you make it too exciting, it won’t be realistic. If you make the thing too realistic, it’ll bore everyone to death. This is always the conflict at the heart of these things. Those About to Die plays around with the timeline, and perhaps portrays Domitian as more of an angry brat that he likely actually was, but the broad strokes feel about right. Roman society is, at this point, reeling from a costly civil war born of its chronic inability to ever sort out the issue of Imperial succession.

The Flavians represented a welcome oasis of stability, but there must have been a sense that Rome’s best days were well behind it and buried with the Julio-Claudians, and that the Flavians were merely substitute teachers from the PE department who could just about handle a few chapters of The Hobbit and wheeling in the telly to put Gregory’s Girl on but who were a little out of their depth when it came to keeping the provinces in line and guaranteeing the grain supply. And it’s out of this miasma of disillusionment, hunger, and boredom that comes all the riots and unrest that characterise the period. It’s fertile ground for television writers, and they use it well: there’s lots of Big Stuff happening all the time. Including Vesuvius blowing off and destroying the coastal towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum and, according to this show, interrupting a gladiator match in Rome some 150 miles to the north, with such ferocity that buildings are damaged and people are thrown to the ground. That’ll be the artistic licence, then.

There is also the depiction of Rome itself: a grand CG-enhanced metropolis that has never looked better on any size of screen. Not since HBO’s Rome have we seen the place so lavishly depicted, in macro-vision via gorgeously expensive looking eagle shots and in the gutters of its winding streets with the rest of the rabble. It’s hot, it’s dirty, every apartment is a tiny and expensive death trap. But by god is it exciting. The atmosphere is infectious, even through the distortion filter of camera lenses, computer graphics, a TV writers room, and twenty centuries worth of myth.

Much of the series takes place at night, though, in an Ancient Rome After Dark where senators can happily walk the streets. This is jarringly ahistorical: Ancient Rome was so dangerous at night that nobody but the most hardened of criminals would be comfortable merely walking around. You were as likely to die from a goods cart fleeing around the corner and flattening you against a wall as you were from a stabbing, which was very likely indeed. Caesar had decreed almost a century earlier that wheeled vehicles were prohibited from moving around the city during daylight, and this was before electric lighting, and so at night Ancient Rome was a pitch black maze of certain death and/or maiming. In the show, it’s basically like the day time except graded a bit blue. This, of course, is fine: it’s not a documentary, it’s TV drama. Night time on telly is for sneaking around, and sexy times. There’s plenty of both in ‘ere, cor.

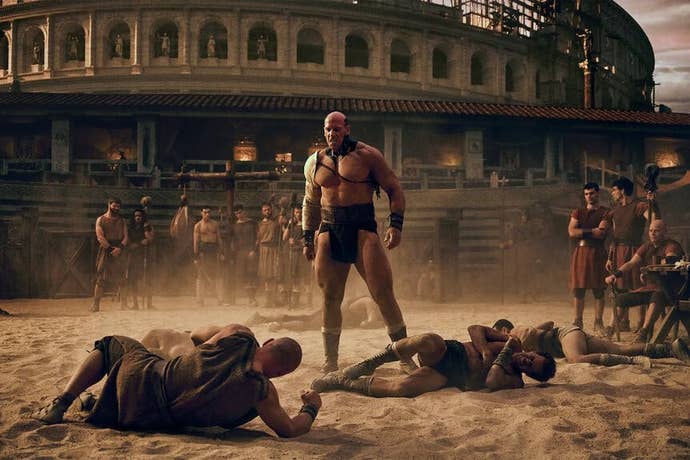

The Game of Thrones comparisons would usually come in about now because, as we all know, that show invented shagging. And it’s worth mentioning here because it is prevalent. In Ancient Rome, life was cheap. Flesh even more so. They were often base, vulgar, and gleeful with it: everyone knows about the dirty graffiti in Pompeii at this point. Similarly with the show’s cavalier attitude to violence. Throats are opened, limbs are liberated from the tyranny of their torsos. Lions just eat guys. It would be shocking had we not seen this dozens of times before, but in a sense, I think Those About to Die is very conscious of that. Sex and violence are graphically depicted, but almost treated with mundane inevitability. This is perhaps most evident in a scene that opens with Domitian watching three of his favourite house twinks going to town on each other. It’s happening, and there’s no ambiguity. Right in the middle of the frame. It’s basically a softcore clip. And it’s not even remotely the most interesting or arresting thing that happens in this sequence: even Domitian himself is bored of it, and seems genuinely pleased to get summoned away to go and deal with some plot.

This isn’t a failing of the show, but part of its commentary on the society it depicts, in my view. In terms of its ratio of writhing gratuitousness vs actual headway being made in the narrative, Those About to Die sits somewhere between the Britishly unsexy I, Claudius – an excellent show where anything that costs money or morals occurs well off camera – and Spartacus, the infamous STARZ joint where the average episode contains more violent deaths than script pages and more shags than a branch of Allied Carpets (also an excellent show). And it knows you’ve seen these things. It knows which bits of Outlander you rewound, you dirty bugger. It knows you’re about as desensitised to pretend violence and sexy times as the Ancient Romans were to the real stuff. At least they had the excuse of there being sod all else to do. You have an Xbox, for shame.

So it’s daft. Epic. Silly. Spectacular. Borderline pornographic, and yet about as sexy as Flavian monetary policy. This feels about right. Ancient Rome in all its hot, wretched, administrative glory, and with the enthusiastic involvement of the guy behind Independence Day and The Day After Tomorrow: someone who knows how to direct for VFX, someone who isn’t afraid to move the narrative around a cool image, or crash-zoom into a name written on a table of gambling odds if that’s the quickest way to shuffle things along. Although it is interesting that he doesn’t direct the episodes where Vesuvius pops off, given how suited he is to the subject matter.

Ultimately, though, what makes Those About to Die so eminently watchable is its humanity. The maternal doggedness of Cala, played with such enormous depth by French actress Sara Martins, is the thread that really ties it all together: the only character with real, tangible stakes. Not power, or wealth, but a simple yearning for her children who have been swallowed up by the Roman system and, even with her help, are unlikely to escape or survive it. Anchored to something so fundamental by a wonderfully believable performance, the world of Ancient Rome locks into place. It reminds us that Domitian loved his brother, despite their political rivalry. It reminds us that the nameless gladiators who spilt their guts to entertain the masses had mothers and sons. These people weren’t uncaring monsters, they were us, and their shortcomings only reflect our own. As do their virtues.

Also there’s loads of Welsh people in it, so it’s good.